Mixed models: handling clusters

keywords power analysis, mixed models, multiple clusters, participant by stimuli

0.8.2

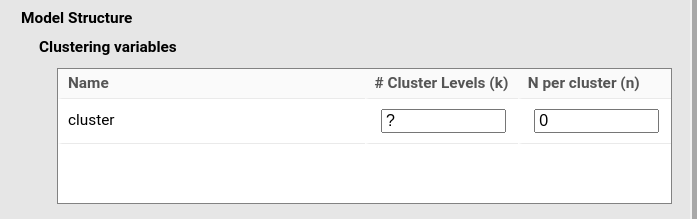

Here we discuss some rules for handling clustering variables

(grouping variables) in different designs. We focus on building the

clustering variables in the correct way and checking the results sample

structure, so we set expected power as the aim of the analysis,

and we fill all cluster variables required sizes (#

Cluster Levels and N per cluster).

When the the aim of the analysis is N (with Find being Number of cluster levels

or Cases within clusters), the rules are the same, but one

of size parameter is left empty. It is also a good idea while

experimenting with different designs to set Algorithm to Raw

approximation which is very fast and does not require us to wait

for a simulation to check the resulting sample structure.

One clustering variable

Simple designs with one clustering variable are defined by specifying in Model Syntax the “bars” component of the formula, such as:

y~1*1+1*x+(1*1|cluster)Note

Hereinafter the coefficients are immaterial for our discussion, so we

always set them to 1 and assume random intercepts only. The sample

structure is not altered by the coefficient values or the definition of

fixed and random effects. We also fill in all the cluster size fields:

# Cluster Levels (k) and N per cluster (n). It

is clear that, depending on the aim of the analysis, one of these

parameters will be determined by the algorithm.

PAMLj reads cluster as

the name of the clustering variable and displays the fields to be filled

in to generate the correct sample based on the cluster variable

definition.

Now, depending on the aim of the analysis, one needs to fill one of

the fields (# Cluster Levels (k) or

N per cluster (n)). Here we discuss the meaning of these

fields, knowing that depending on the goal of the analysis, one of them

will be the target of the power function.

With one clustering variable, # Cluster levels (k) is

the number of groups clustering the observations. In a multilevel

design, say with pupils clustered within classes,

# Cluster levels (k) is the number of classes in the sample

(or the number to be established by the power analysis). In a

repeated-measures design with conditions repeated within participants,

# Cluster levels (k) is the number of participants.

N per cluster (n) is the number of observations within

each cluster level (group). In a multilevel design with pupils clustered

within classes, N per cluster (n) is the (average) number

of pupils in the sample (or the number to be established by the power

analysis). In a repeated-measures design with a condition repeated

within participants, N per cluster is the number of

measurements taken for each participant.

One-way repeated-measures ANOVA design

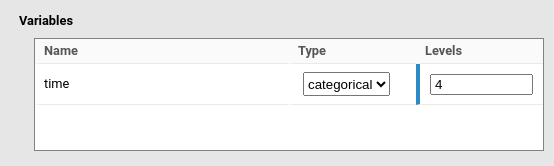

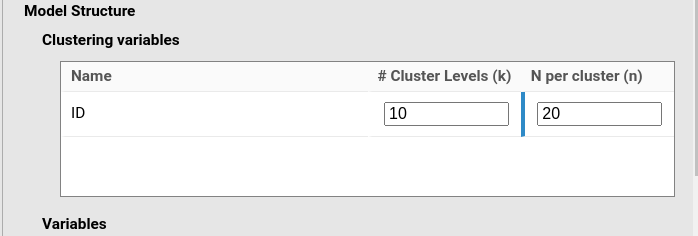

Assume we have a repeated-measures design with four time points (see an example in Mixed vs RM-ANOVA), and one measurement per participant (identified by the variable ID) at each time point. To define this design, we would input:

y~1*1+[1,1,1]*time+(1*1|ID)Then we specify that time is a categorical variable with

4 levels.

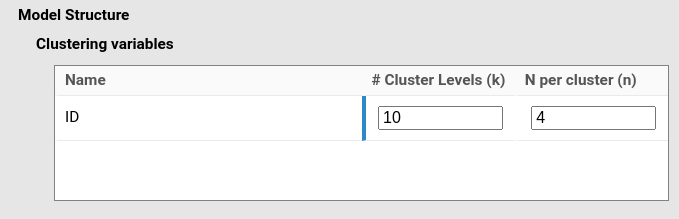

and we set the cluster N per cluster to 4, indicating

that one participant (the cluster unit) has 4 observations (we assume

here we have 10 participants (\(k=10\)), but if the aim is N we would leave

\(k\) empty).

The resulting data look like this:

y time ID

1 0.64342217 1 1

2 0.15874249 2 1

3 -0.70961322 3 1

4 -1.46269242 4 1

5 -0.80773575 1 2

6 0.38518147 2 2

7 -1.95162686 3 2

8 2.98249154 4 2

9 -0.04821753 1 3

10 -1.61386528 2 3

11 -0.68877198 3 3

12 1.33885528 4 3We can see that time is repeated within ID, with one measurement for

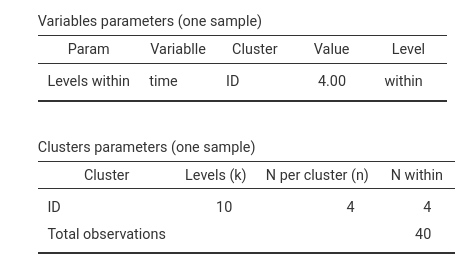

each level of time. Table Variable parameters (one sample)

also shows that we are simulating the correct design, because

time has 4 levels (column Value) repeated within

cluster ID.

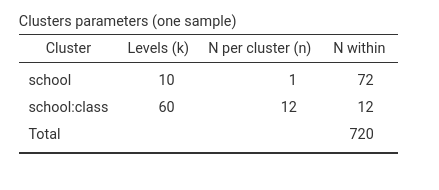

In terms of clusters structure, table Cluster parameters

shows that ID has 10 levels, with 4 observations with each

cluster, and 4 observations within, yielding 40 observations in total.

Whereas in this case the N per cluster (n) and

N within may seem redundant, there are many design

structures in which the two columns conveys different information.

Note

To see the tables reporting on sample charateristics, select the option Variables structure in | Options panel. Clusters structure produces a table with information about the variables and their levels. To see an example of the data generated by your model in PAMLj, select Data structure.

Assume now we have a similar design, but within each time condition the participant is measured 5 times (5 trials). We still have the same model:

y~1*1+1*time+(1*1|ID)and the same variable definition (time with 4 levels), but now

N per cluster is 20, which is 4 levels of time × 5

trials.

The resulting data look like this (first participant):

y time ID

1 0.38563267 1 1

2 1.24833377 1 1

3 -0.76549380 1 1

4 -0.94633446 1 1

5 0.72747486 1 1

6 -0.58658441 2 1

7 -1.01631241 2 1

8 -2.66731584 2 1

9 0.62401507 2 1

10 0.15654240 2 1

11 -0.26135861 3 1

12 0.11923442 3 1

13 0.66327673 3 1

14 -0.63811091 3 1

15 0.31462810 3 1

16 0.27796168 4 1

17 0.32836307 4 1

18 -0.34867872 4 1

19 -0.20470434 4 1

20 -0.71480958 4 1The variable structure is the same as the example above (4 repeated measures), just observations with each participant are now 20 and thus the total number of observation is 200.

Note

Notice that categorical variables are built to vary within clusters by default. This behavior is chosen because in power analysis for mixed model within-cluster variables are more common. However, PAMLj allows to specify between-clusters categorical variables (and also continuous variables). Please read Mixed models: Building factorial designs for help on that.

Multi-cluster designs

Here we discuss cases with more than one clustering variable. When more than one cluster variable is involved, things gets a bit complex (I dare I say wild), but still those designs are doable in PAMLj. One needs a bit more patience to get it right.

Two cases are most relevant for researchers: cross-classified clustering and nested clustering.

Cross-classified clusters

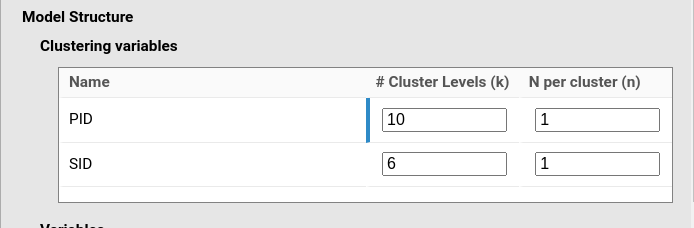

A typical example of cross-classified clustering is an experimental design in which \(P\) participants (identified by the variable PID) are tested with \(S\) stimuli (variable SID). Every participant is exposed to each stimulus, and each stimulus is seen by all participants. We start with the simpler example in which there is only one measurement for each combination of participant and stimulus (a participant sees a stimulus only once).

The mixed model is:

y~1*1+1*x+(1*1|PID)+(1*1|SID)Let’s say we want a sample of 10 participants and 6 stimuli. In total

we have 60 observations, in which each participant has

N per cluster (n) equal to 1, and each stimulus has

N per cluster (n) equal to 1 as well. It may seem counter

intuitive, but the participant is actually repeated only once, but their

measurement is spread across 6 stimuli. Thus, we need to set:

The resulting data (first participant) will look like this:

y PID SID

1 0.741008569 1 1

2 -1.001295926 1 2

3 0.728456584 1 3

4 0.649785351 1 4

5 -1.373459856 1 5

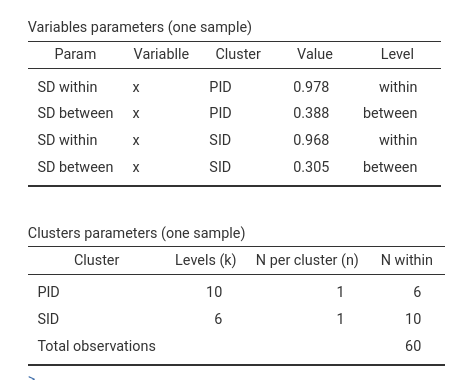

6 -2.073459856 1 6In the Clusters parameters table we can see that we have

6 observations with each participant (PID), because each

participant sees 6 stimuli, and 10 observations within each stimulus,

because each stimulus is seen by 10 participants.

Notice, however, that the independent variable x is continuous, and it is left to vary both across and with clusters by default. For dealing with multiple clusters variables with between vs within independent variables, please see Mixed models: Building factorial designs.

Nested cluster classification

Note

In mixed models estimated following the R package

lme4 syntax, the expression

(1 | school/class) is just a shorthand for specifying

nested random effects. The operator school/class expands

internally into two terms: one random intercept for the grouping factor

school, and one random intercept for the interaction (i.e.,

nesting) school:class. Formally, the random structure

is:

(1 | school) + (1 | school:class)This means that we estimate one random intercept (or whatever random

coefficient we include) per school, and one random intercept per class,

and class are uniquely identified by che combination of school and

class. Accordingly, the Effect size indices table indicates

that the cluster variables are school and

school:class.

The general rule is that, in mixed models, “nesting”

is not a separate statistical concept—it is only a syntactic shortcut.

What matters is the definition of the grouping factors, which in this

example are school and school:class. Random

coefficients (whatever they are) are computed across the groups defined

by these two variables.

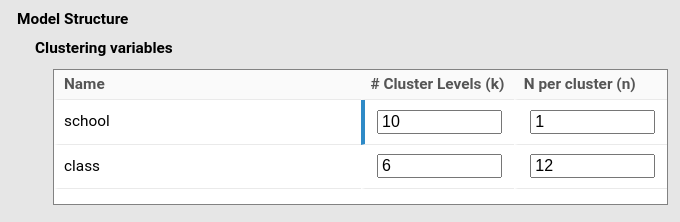

Here things get ugly: Let us consider one of the classic multilevel design: pupils within classes within schools. In this design we have two clustering variables: class and school. In multilevel terminology, pupils are level 0, classes are level 1 with pupils nested within classes, and schools are level 2 with classes nested within schools. To be practical, let us assume we want a sample with 10 schools, each with 6 classes, and each class (on average) with 12 pupils.

First, we set the model:

y~1*1+1*x+(1*1|school/class)Then we specify that we have 10 schools, each with 6 classes, and each class has 12 observations (pupils).

The generated data look similar to the cross-classified data:

row y x school class

1 0.456717064 -1.017673137 1 1

2 -1.495551991 0.694440645 1 1

3 -0.480543438 0.194002872 1 1

4 0.293003240 -0.116523555 1 1

5 -1.702547420 -1.203825265 1 1

6 1.014035495 0.461345298 1 1

7 -0.415440850 -0.585482460 1 1

8 -1.524924282 0.544323536 1 1

9 -0.106578314 -0.196693360 1 1

10 -0.035543818 -2.741920747 1 1

11 0.229491601 0.170131727 1 1

12 -1.909614050 -1.159812029 1 1

13 1.190966855 -0.356247480 1 2

14 -2.028748115 0.489991721 1 2

15 -1.079830560 1.315918615 1 2

16 0.099924682 -0.330729467 1 2

17 -0.075449795 -2.424778270 1 2

....However, the estimated model is different as compared with the

cross-classified design. If one looks at the

Clusters parameters table, one finds that the clusters are

now school and school:class, which is exactly

how the model specification expands.

In terms of cluster size, we obtain the results we intended. Let’s check if the setup is correct: each school has 6 classes with 12 pupils, so within each school there are 72 observations. Within each class nested in school there are 12 pupils. But how many observations we’ll have in the sample? Well, 720, because we have 72 observations per school and we have 10 school (\(72 \cdot 10=720\)), or , equivalently, 60 classes with 12 pupils (\(60 \cdot 12=720\)). So, the data are ok.

Apparently nested desings

(Here things remain ugly, and computation gets very slow)

A good rule of thumb in mixed models is that when you are in

doubt about how the clustering variables are related, they are probably

not nested. The second rule is that if nesting (i.e

|cluster1/cluster2) does not come intuitively, things get

clearer if one explicitly thinks in terms of combinations of clusters

levels. The third rule of thumbs is: clusters defined in different

blocks ((1|cluster) being a block) are

cross-classified.

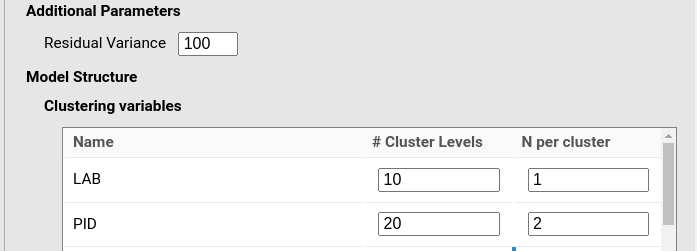

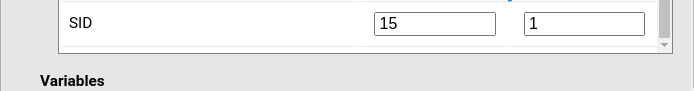

Consider the following design. We have 10 labs (LAB) (or any number you like), each lab conducts an experiment with with 20 participants (PID), each responding to 15 stimuli (SID). Thus, apparently we have a cross-classified experiment nested within labs. What this design actually means is that each level of labs has all 20 X 15 observations corresponding to the cross-classified clustering we have seen above. Thus, we do not have nesting at all, but simply a 3-way classification. Assume the experiment involves a dichotomous factor (cond) with two levels, repeated within-participants. That is, each participant respond to the 15 stimuli in two different conditions.

Now we have to think carefully: we have 10 unique labs, so each labs

requires a random intercept: (1|LAB). Than we have 20

participants for each lab, and each participant is uniquely identified

by being in a particular lab (participant 1 in lab 1 is different than

participant 1 in lab 2): (1|LAB:PID). Stimuli, however, are

not different across labs, because each lab uses the same stimuli. Thus,

we need one random intercept for each stimulus (SID), and they are not

identified by being in a particular labs. Thus: (1|SID)

To set it up, we simply need to specify 3 clustering variable, LABS, PID and SID and their variances in the model.

y~1*1+1*cond+(1*1|LAB)+(1*1|LAB:PID)+(1*1|SID)Now we focus on clusters size. We have 10 labs, each labs is

“measured” once (there is only one experiment per lab). Thus

# Cluster levels=10 and N per cluster=1. We

have 20 participants, each participant sees the stimuli 2 times (one per

condition), so we have # Cluster levels=20 and

N per cluster=2. Finally, we have 15 stimuli, each stimulus

has one replication (one version), so # Cluster levels=15

and N per cluster=1.

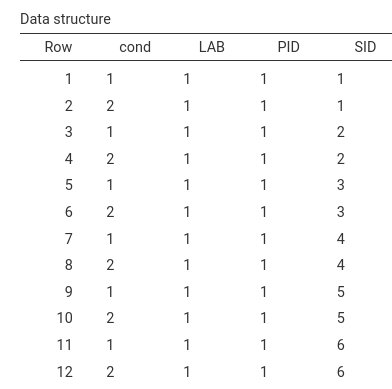

This is the resulting sample structure (first rows of the generated dataset):

`…

It is clear that each lab has all PID (here not visible) and each

participants sees each stimuli twice, in cond=1 and cond=2. To

appreciate the full sample characteristics we can look at the

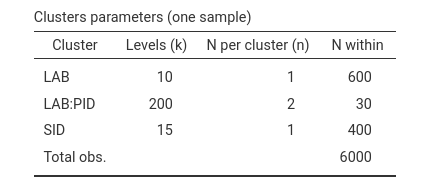

Clusters structure table:

Each participant, identified by the combination LAB:PID

has 30 observations, because it sees 15 stimuli twice. Each stimulus is

seen by 20 participant twice in 10 labs, so each stimulus has 400

observations. Within each lab, however, the experiment implies \(20 \cdot 15\) observations, so each lab has

600 observations. Finally, the 600 observations per lab, summed across

10 labs, yields 6000 observations in total.

Understanding the output design

In all the examples above we set the clusters parameters

(# Cluster Levels (k) and N per cluster (n))

because we focused on understanding how the different parameters yild a

given sample structure. Let’s try now to change the aim of the analysis

to aim:N and Find: Number of cluster levels.

For simplicity, let us assume that we are looking for the minimum number

of labs (LAB) required to obtain a power of at least .90. To

replicate the simulations, let set the Residual

Variance parameter to 500 and use raw approximation

as the finding algorithm.

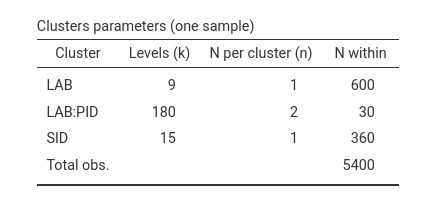

Running the analysis with these parameters, one obtain (with a small

variability) a Cluster Levels (k) equal to 9. So, given all

the other parameters, we need 9 labs to get at least a power of .90.

Let’s see what the structure of the data is.

Does it make sense? We need \(9\)

labs, and each experiment requires \(600\) observations. Each participant,

identified by the combination LAB:PID has \(30\) observations, because it sees \(15\) stimuli twice, but now there are \(9\) labs, so the participants are \(20 \cdot 9= 180\), and within each

participant we still have \(30\)

observations as in the previous example. The \(15\) stimuli (SID) are seen by

\(180\) participants twice, so \(180 \cdot 2=360\). Pretty good sense, it

makes.

A variant

What if, however, each labs uses different stimuli. For instant, if

the stimuli are words and different labs conduct the experiment in

different languages, each unique stimulus is identified by the

combination of LAB:SID. Thus, we need to cast this

information in the model. The remaing input definitions are the

same.

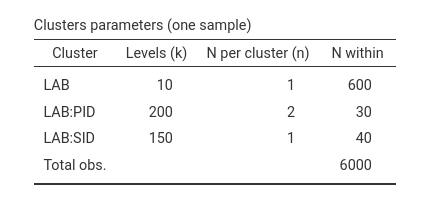

y~1*1+1*cond+(1*1|LAB)+(1*1|LAB:PID)+(1*1|LAB:SID)

Coherently, we still have 30 observation per participants, that are

200 in total. Each of the 10 labs has 600 observations. Now, however, we

have 150 stimuli (LAB:SID, 15 stimuli for each of the 10

labs), each with 40 observations within (20 participants see each

stimulus twice). The total number of observations are still 6000.

Additional material

Examples

Some worked out practical examples can be found here

Comments?

Got comments, issues or spotted a bug? Please open an issue on PAMLj at github or send me an email